Table Of Content

(He wrote to Claud Cockburn on 15 April 1966 of Melvin J. Lasky, the driving force of Encounter, that 'Lasky I regard as a sort of cultural cold war conman'.) Encounter retaliated with a comparison of its accuser with Senator Joseph McCarthy. O'Brien wrote a reply for the New Statesman, which, when threatened with a libel suit, pulled the article. He issued libel proceedings in Dublin, which Encounter settled on the day of the hearing in February 1967. O'Brien first attended Miss Haines, a protestant preparatory school, but transferred to the Dominican nuns in Muckross on Marlborough Road before his first communion. If that reflected his father's wishes, his taking Irish rather than Greek as he had wanted to conformed to his mother's. From our tiny island of Enlightenment (haskala), we could peer out into that possibly enviable fog' (ibid., 19).

Holy War Against India

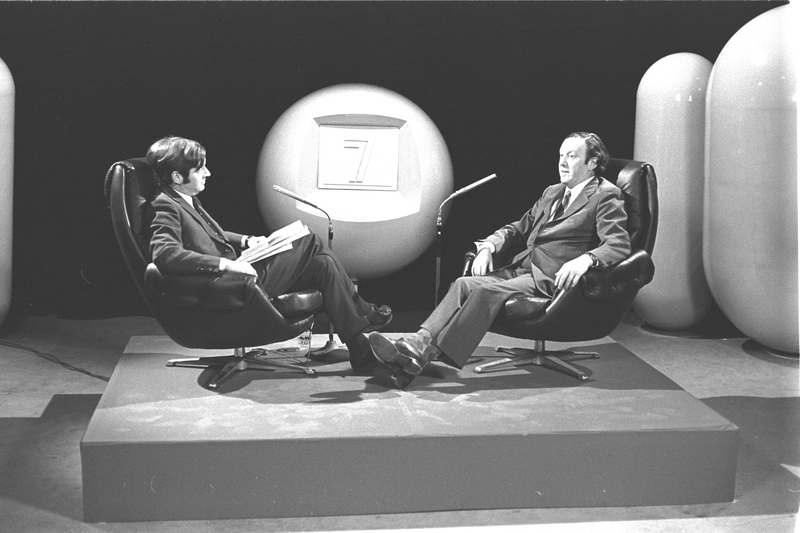

O’Brien was a dramatist, newspaper editor and prolific contributor to the Atlantic, the New York Review of Books and other publications. O'Brien added lustre to the Observer, but the division of authority between editor and editor-in-chief was operationally fraught. O'Brien had a dispute with the distinguished journalist Mary Holland (qv), who was the paper's Irish correspondent, in relation to a feature on a republican family in Derry, in which he wrote to her that he thought it 'a serious weakness in your coverage of Irish affairs that you are a very poor judge of Irish catholics. That gifted and talkative community includes some of the most expert conmen and conwomen in the world and in this case I believe you have been conned.' Holland resigned, rejoining the paper after O'Brien's departure (O'Toole, Magill (June 1986)). When de Valera returned to power at the 1951 general election, Frank Aiken (qv) became minister for External Affairs. O'Brien remained in charge of the Irish News Agency, which had a diminished role under Aiken, and became the department's link to the nationalist community in Northern Ireland, to which he made a number of visits.

Israeli strikes intensify across Gaza as fresh evacuations ordered in north of enclave

In an undergraduate career marked by intense pre-examination sprints rather than the steady pace favoured by his friend and rival Vivian Mercier (qv) (whom he consistently 'pipped'), he won great distinction. In his first year he won a foundation scholarship, and thereafter the unusually remunerative Hutchinson Stewart literary scholarship. Once described by the social critic Christopher Hitchens as “an internationalist, a wit, a polymath and a provocateur,” Mr. O’Brien was a rare combination of scholar and public servant who applied his erudition and stylish pen to a long list of causes, some hopeless, others made less so by his combative reasoning.

EDITOR

The party included Brian Urquhart, soon to succeed O'Brien in Katanga, who was bloodied with a rifle butt and dragged away along with two others. Manhandled, Máire MacEntee acted with calm and resourcefulness, no less than O'Brien's driver, Private Paddy Wall. He wrote, still as Donat O'Donnell, for Commonweal in the US and reviewed for the Spectator and the New Statesman in England. He completed his doctoral thesis on Charles Stewart Parnell (qv) and his party.

He, therefore, ‘reluctantly’ offered his resignation as ‘spokesman on Foreign Affairs’.Footnote 82 In fact, Halligan and his colleagues never met Callaghan in an official capacity. Nor did they hold any official meetings with ‘any Labour Party officials’, as pointed out by Corish in reply to O'Brien's letter of resignation. Rather, Corish had run into Callaghan ‘by accident’ in the hotel that the former was staying in.Footnote 83 Following much arm twisting, which included the personal intervention of Frank Cluskey, O'Brien rescinded his letter of resignation.Footnote 84 The signs, however, were ominous.

O'Brien was in his 40s when he entered into the most fateful and controversial chapter of his life – his posting to the Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) by the direct initiative of Dag Hammerskjold, then secretary-general of the UN. He arrived in Elizabethville, the capital of Katanga province, in June 1961 to find himself in the epicentre of an international hotbed. The secession of Katanga, the murder of the first prime minister Patrice Lumumba (often ascribed to European-paid mercenaries), the dubious role of Union Minière, made the front pages of the world press for months on end. In the end O'Brien, apparently acting on what he thought was a UN resolution, ordered the UN peacekeeping force into action against the mercenaries and against Katanga's secession. The crisis became semi-farcical when the poet Máire MacEntee (daughter of a Fianna Fail minister) arrived to join him and declare her support. At the end of 1955, O'Brien's direct involvement in the Irish government's anti-partition campaign ‘ceased’, following his appointment to the Irish embassy in Paris, as a counsellor.Footnote 40 The following year, he was appointed the head of the United Nations section of the D.E.A. in Dublin, reporting to Fredrick H. Boland in New York.

Save article to Google Drive

If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account.Find out more about saving content to Dropbox. 47 O'Brien first came into direct contact with the Northern Ireland civil rights movement in late October 1968 when he addressed a gathering at Queen's University Belfast on the subject of ‘Civil disobedience’ (O'Brien, States of Ireland, p. 152). For further analysis of O'Brien's attitude to the civil rights campaign in Northern Ireland, see Whelan, Conor Cruise O'Brien, pp 134–40. In a complex arrangement promoted by David Astor, who had relinquished ownership of the Observer to Robert Anderson of Atlantic Richfield, and brokered by Arnold Goodman, O'Brien was appointed editor-in-chief of the Observer, with Donald Trelford remaining editor. By the following month it was decided O'Brien would contest Dublin North-East, which encompassed Howth, and he was quickly inducted into the Howth branch of the party.

Katanga, 1961

Politically O'Brien's principal contribution to Irish politics lies in his sustained attack in the 1970s on the terrorism of the IRA, and on the moonlit penumbra of condonation and evasiveness that surrounded it in southern politics. He understood that this had to be an assault of great intellectual clarity and measured passion, and consciously situated his argument in the line of great controversies from the fall of Parnell, something conveyed in the presence of Yeats in what he wrote and said. It was important for this that he should have been a member of Dáil Éireann in 1969–77 and of the Irish government of 1973–7. It is difficult to convey now the ferocity of the intellectual ferment that this generated, or its salutary consequences for democratic politics in the Irish state.

Against some sharp cavilling from Robin Dudley Edwards (qv) as extern examiner, he was awarded a doctorate in 1953. His thesis was published as Parnell and his party by the Clarendon Press in 1957. Historiographically it was almost revolutionary in its critical analysis, acuteness of insight and scholarly dispassion. O'Brien was conscious of the transition from oral remembrance, dedicating the book to the memory of David Sheehy and Henry Harrison (qv), the two survivors of Commitee Room 15 he had known.

He was wafted up in a lift, only to find himself confronted by a modern-day equivalent of Oscar Wilde's Lady Bracknell. "I assume," this apparition remarked, after looking him up and down with some distaste, "you must be someone to see Lord Goodman." To Conor it felt as if the floor had opened and swallowed him up. "But I learnt one lesson - that my place in the English social order would never be secure." To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account.Find out more about saving content to Google Drive. To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies.

Christopher Hitchens · The Cruiser - London Review of Books

Christopher Hitchens · The Cruiser.

Posted: Thu, 22 Feb 1996 08:00:00 GMT [source]

O’Brien spent much of his early career in the Irish foreign office, and his experiences in Congo in 1961 transformed him into a widely known public figure. He had gone to Africa to prevent the secessionist effort in Congo’s mineral-rich Katanga province. He drew attention for his accusations that several European countries, including Britain, were tacitly in favor of the secessionist effort. He also accused the Congo’s interior minister of a “murderous conspiracy” against U.N. He was the most commendable of colleagues, holding us all rapt in local hostelries as his voice rose by something like an octave as the glasses piled up in front of him.

From an interview with Harry Kreisler that appears on the University of California at Berkeley Web site, one gets a brief glimpse at those contradictions and its effect on O'Brien's career. His mother was a strong Irish Catholic; his father (whom O'Brien—at the age of ten—watched die) was an agnostic who disapproved of Catholic education. "One third of the pupils were people of Catholic origin like myself, but somewhat detached from that background," O'Brien commented to Kreisler. Later, as a vocal intellectual, he saw no place for Sinn Fein, the IRA’s political wing. He was strident about political self-determination and saw no real hope or need of a united Ireland, noting that the 1 million or more Protestants in the north had no interest in joining the Irish Republic.

Conor Cruise O'Brien - The Telegraph

Conor Cruise O'Brien.

Posted: Fri, 19 Dec 2008 08:00:00 GMT [source]

At a 1967 Vietnam War symposium O'Brien clashed with Hannah Arendt, who had remarked, "As to the Viet Cong terror, we cannot possibly agree with it". O'Brien responded, "I think there is a distinction between the use of terror by oppressed peoples against the oppressors and their servants, in comparison with the use of terror by their oppressors in the interests of further oppression. I think there is a qualitative distinction there which we have the right to make." Lumumba had been trying to solicit Soviet support for his military campaign to stop Katanga breaking away, which drew the wrath of the United States. One reason given for the interference of the western powers was that they feared the Soviets would exploit the Congo's rich uranium deposits for making nuclear weapons. Washington, Westminster and Brussels have all been implicated in Lumumba's execution at the hands of a firing squad assembled by the Katangan authorities. The man who would become widely known as 'The Cruiser' grew up in the Dublin suburb of Rathmines, the son of a journalist father and a crusading feminist writer mother.